On Finding One's Guru/Lama

The third of four posts on the spiritual mentor: establishing the foundation.

Establishing a relationship with a Tibetan Lama (a spiritual mentor) is probably a different matter for every student. I can only share my experience and that of my wife, Kayla, but our experiences may prove helpful to others, so this is rather a long post.

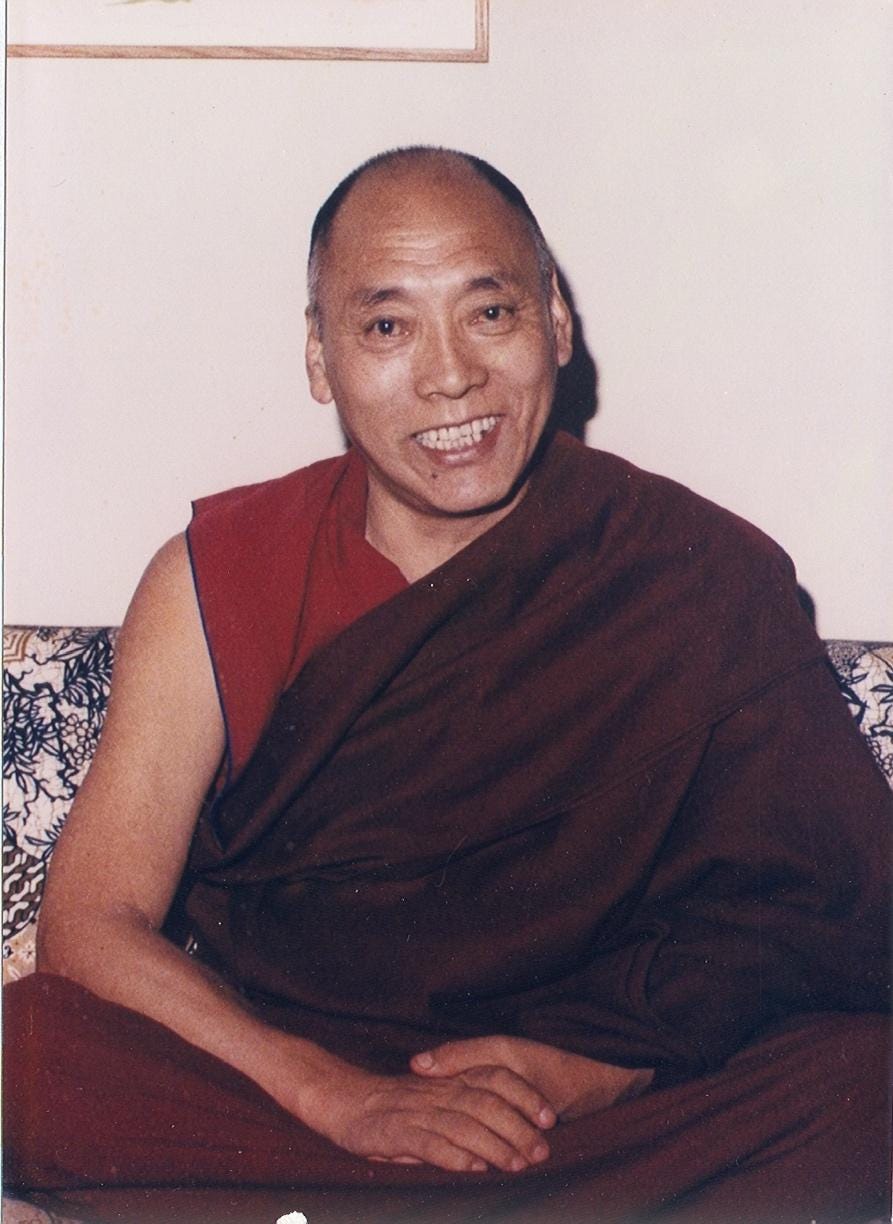

Not all meetings with lamas are either cryptic koans (like one of my meetings with the Dalai Lama), or profoundly transformative (like my meeting with Ling Rinpoche). Sometimes they begin very mundanely and grow and ripen over the years. The meetings follow a slow sequence as they penetrate one's mind, like a fine nutrient which sustains one’s growth. My relationship with Tara Tulku Rinpoche was like that.

It began at the ending of my second trip to Dharamsala, some time after meeting with Ling Rinpoche, and our first meeting seemed to be without any particular significance. The Seventy Stanzas had been re-translated and I had collected Geshe Sonam Rinchen's oral commentary on it. I would return to my job in the Amherst College administration to edit Geshe-la's commentary as well as the transcripts of my interviews with the Dalai Lama during my spare time.

What I didn’t know at the time was that Professor Bob Thurman, who was in the Religious Studies department at Amherst College, had asked the Dalai Lama for a teacher of Ghuyasamaja Tantra. His Holiness had selected the retired abbot of Gyuto Tantric College: Tara Tulku Rinpoche. In rather typical Thurman fashion Bob organized the opportunity for their tutorials by arranging for Tara Tulku to be the Luce Visiting Professor of Religion at Amherst College, thus funding his travel and residence in Amherst for six months.

Merely knowing of Rinpoche’s appointment, I decided to pay him a visit and offer my assistance in case he might have some difficulties with travel, the American embassy, or whatever. Rinpoche was staying in the home of His Holiness' tailor when I visited him. When we met he offered me a yellow scarf, which had been given to him by his previous visitor. He was simply passing it along, but nevertheless, he said that “it is very auspicious for you to receive it.” As usual with such things I had no idea what he meant. In no obvious way did our meeting seem significant to me. We parted in a friendly fashion and I went back to winding up my translating work with Geshe-la.

Reflecting on my difficulties with the translation project I asked Geshe-la if he would teach me to meditate on Manjushri, the bodhisattva of wisdom. I figured that practice would help me with the editing of the oral commentary which awaited me over the coming year. "No" he would not, he replied, without any particular explanation as to why. Only much later did I learn that because his own teacher was in residence at the Library of Tibetan Works and Archives, protocol required that I request the initiation from him instead. But at the time I was merely mystified.

My return to Amherst was difficult for multiple reasons. My wife and I separated, and she moved to Manhattan. Suddenly I was a lonely 37 year old bachelor in a community of undergraduates and mature married couples. So when Tara Rinpoche came to Amherst my life was a shambles on a personal level, although it was inching forward on an academic level. I began to spend as much time as possible with Rinpoche. That turned out to be more or less daily, because I attended all the classes he taught at the College, as well as the teachings he gave at the temple in the attic of Bob’s house.

About a month into his visit I approached him and asked if he would teach me to meditate on Manjushri. He replied “No” without further comment, just as had Geshe Sonam Rinchen. Again, I was mystified. Recalling popular spiritual lore, I thought that I needed to ask three times to get a favorable answer, but instead I got another “No” and then yet another “No.” That made my sense of unworthiness complete and I descended ever more deeply into the darkness as the loss of my marriage, my loneliness and the Massachusetts winter coincided.

Rinpoche had said that he would not teach me to meditate on Manjushri, but unbeknownst to me, he simply was the embodiment of Manjushri if only I could have seen it, though I could not at the time. One winter night a number of us were gathered in Bob’s attic temple listening to Rinpoche talk about the Buddhist theory of emptiness (shunyata) and dependent origination, which were two sides of a single coin, as it were. Of course I thought I knew a lot about that, as I’d been working through Nagarjuna’s teachings on the subject with Geshe Sonam Rinchen. But when Rinpoche talked about the snow storm raging outside, about the kindness of the workers who were clearing the streets for us so we could walk or drive home and how our ability to conduct our lives was totally and, in every moment, dependent on others in just such a way I had an insight into the actuality of dependent origination which had utterly eluded me until that moment. Geshe-la’s teachings had been intellectual in character, and had ripened my mind, but in that moment in Rinpoche’s presence a sprout had emerged from those seeds. I saw what I had only intellectually understood. As I would eventually understand from my meeting with Ling Rinpoche, the impact of the teachings of a lama who has realized what he teaches is far beyond anything merely intellectual. Though it would take me years to realize what had happened, Tara Rinpoche had taught me to meditate on Manjushri by ripening the seeds of Manjushri’s wisdom mind within me. But realizing this would require that first I leave New England for San Francisco for a new job, a new life and a new wife, and then for the two of us to undertake a retreat with Rinpoche in Bob’s attic.

Tara Rinpoche left Amherst at the end of the winter of 1983/4. All that academic year I had been trying to find a full-time teaching position, but without any success. I had only come to New England because of my wife’s internship at Mt. Holyoke College and I began to wonder why I was staying. I never felt comfortable in the eastern USA -- circumstances simply kept me there. Without finding success in what I wanted to do, I thought, why not just "roll the dice" and go back to San Francisco, which is where I had always wanted to be anyway and look for an administrative university job.

When I rolled the dice they came up a lucky seven because after a few weeks on the job hunt I found an administrative position at Stanford University. It was not the sort of position I really wanted, but it paid the bills while I searched for the sort of job I did want. And I found a plumb. John F. Kennedy University, located on the east side of the Berkeley hills, recruited me to be the Dean of its Graduate School of Consciousness Studies. The post went with a faculty appointment. My experience in faculty administration at Amherst and my degrees in Counseling Psychology and Religious Studies had made me a perfect fit for a really unusual job. It would be packed with financial and personnel challenges, but it also would put me in touch with many of the leading thinkers who were working at the intersections of Psychology and spiritual life. And, as it turned out, it would give me tremendous control over my time.

A month or so before taking up this new post, I was looking at the notices on a bulletin board of a Buddhist center in Berkeley and saw a poster advertising lectures that Tara Rinpoche would be offering at San Francisco Zen Center's Green Gulch Farm, which is located on the coast north of the city. In fact, he was lecturing at the time I saw the poster. Breaking every speed limit, and miraculously avoiding the police, I arrived at his talk just as it was winding up. Rinpoche took one look at me and lit up in a huge smile. I embraced him, he pulled my beard with affection and we headed off to his room to catch up with each other. I was completely unaware of a blond woman in monastic robes sitting in the audience -- Kay, my wife to be.

The next day I met with Rinpoche, which was his last day at Green Gulch. He told me that although he was about to leave for India, he would return to the USA in two years, and that at that time he would teach me to meditate.

Fate and karma began to stir things up. The blond woman in monastic robes had had her own meeting with Tara Rinpoche, had on that very day (!) become his disciple and had received his blessing to do the meditation practice of White Tara, a female form of the Buddha. Recently widowed, she was spending a year at Green Gulch trying to get her life sorted out. During that time she had the opportunity to take instruction from many visiting teachers but none of them touched her as deeply as did Tara Rinpoche.

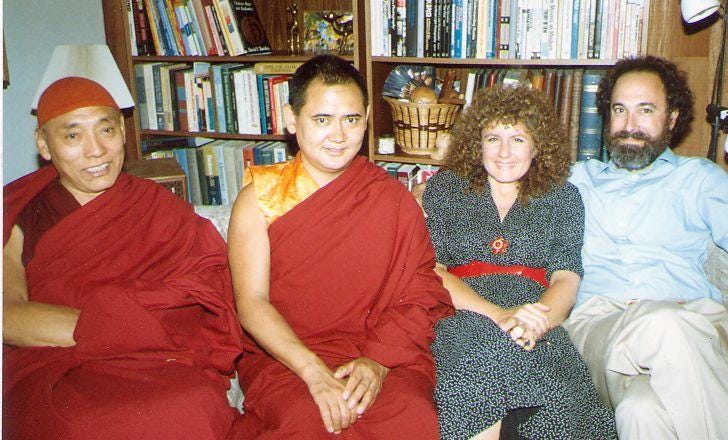

It took about six months before a mutual friend organized a “blind date” with Kay. She had been looking for a partner who shared her commitment to Buddhism. I was looking for a spiritual partner as well. A psychic had told Kay that she would meet someone who glowed and who was a leader in the community. When we met I had been drinking beer with our mutual friend and though Kay claims she recognized my spiritual glow as soon as we met, I have always suspected it was merely the beer. Whatever the case, we were immediately interested in each other. Things moved quickly and within a few months we were sharing a house in San Francisco with an expansive view of the Pacific. In a year we were married. I had almost everything I had been seeking. The missing piece was a fruitful spiritual practice that Kay and I could share.

Even that was soon to appear. Bob Thurman requested my assistance in sponsoring Tara Tulku's next visit to the USA. The American consulate was balking at giving Rinpoche a visa for a teaching tour and an invitation from a dean at my university would help pave the way. I was more than glad to assist and began to prepare for his visit.

The first part of Rinpoche's 1988 tour to the USA was to be a month-long retreat in Bob's attic temple. Kay and I flew out to Amherst, not really knowing what to expect beyond the fact that Rinpoche would be teaching us to meditate. In fact it did not matter too much to me just what form of meditation he would be teaching. The five years I had known him had ripened my devotion and faith in him. Perhaps the need for that ripening had been the reason he had refused to teach me when I made my first request. Kay's devotion had been immediate, and he had given her the Tara initiation and taught her the Tara meditation on the day she requested a practice. I suppose I was a tougher nut to crack.

It took me twenty years from the time of the Amherst retreat to understand that ripening process more fully. During those years I was often requested to teach meditation and refused. But eventually, after some resistance, I agreed and have since found that the level of commitment required for successful meditation practice is quite hard for my students to achieve. The demands of daily life and the vagaries of the mind make commitment quite difficult, and inner impediments are hard to overcome. Faith in the directions of a teacher make progress possible, and I have seen that without this faith deep practice is hard to achieve. I was fortunate that Tara Rinpoche had had the wisdom to understand how to generate my faith in him. Without it I doubt that I could have maintained the effort for cultivating the meditation practice he gave me at the Amherst retreat. Finding a teacher with such wisdom is rare and perhaps that is why few students can dive really deeply into spiritual life. I of course do not have his level of realization and cannot inspire students with faith as he could.

The retreat established the basis for Kay’s and my ongoing meditation practice, but engaging in the practice on a daily basis would be a challenge when Kay and I returned to our working lives in San Francisco. We were encouraged in our practice when Rinpoche stayed with us later in the summer. His visit to Kennedy University for a public lecture was part of the deal which had gotten him into the country and we were supremely fortunate to host him in our home.

After a week with us, he left to complete his teaching tour. But before leaving he invited Kay and I to come and do a second retreat at his monastery in Bodh Gaya the following January. I could not believe I could have such good fortune not only to have the opportunity to do a retreat with my lama at the site of Buddha's enlightenment, but to have a job which would give me the freedom to travel. And when we came to do the retreat, circumstances were even more remarkable than we might have imagined, for there were only four students doing the retreat, and Rinpoche sat with us for the four sessions each day. Between sessions we stretched our legs by doing circumambulations of the Buddha's enlightenment stupa. When the retreat ended Rinpoche took us on a day-long pilgrimage to some of the area's holy places, including Vulture Peak, Mahakala's cave and the ruins of Nalanda monastery.

In the next couple of years we were able to do two more retreats with Rinpoche The first of those retreats also had a real intimacy, as we all shared a single house. This gave us an opportunity to see elements of the maturity of Rinpoche's practice we had not witnessed before. Between meditation sessions we would sit in the garden together or take walks. As he would stroll along he would constantly reach out and touch the leaves of the shrubs. He would also snap his fingers every few minutes. When we asked why he was snapping his fingers he replied that "It is to help me remember emptiness." Perhaps the touching of the leaves was a way of remembering his interconnectedness to all things, the dependent arising of everything.

At the end of this retreat Kay and I met with Rinpoche for some advice, during which he made a comment that mystified us: "Now the suffering begins." We continued to wonder about this during the next month-long retreat which began about a month after that meeting. Less than a year later we heard from Rinpoche's attendant that he had inoperable stomach cancer and would not live much longer. Now we knew what the suffering was about.

Circumstances at the university prevented me from going to India to see him a last time, but Kay had a dream that she should go. It fired her motivation to overcome all the obstacles and uncertainties of a sudden trip to India. And perhaps it was good that I stayed behind and made her travel arrangements while she was in motion, because she arrived in Dharamsala and was able to see Rinpoche on the last day he took visitors. Rinpoche had been one of those large Tibetans that the Kham region produced, but now he was all skin stretched over bones. But he was luminous at the same time. In Tibet he had been known as a fierce and formidable debater, but now only his sensitive compassion shown forth, even through his suffering. "Why have you come?" he asked Kay. "To see you one last time and tell you of my gratitude for your teachings." Conserving his voice, he smiled and gave her a thumbs up sign. "You should see the Dalai Lama to find out what you and David should do next for your practice." Through all his sickness his concern for his students never ceased.

The next day he would take no visitors, and the following evening he died. It seemed that most of Dharamsala attended his cremation ceremony; he was deeply beloved by the community.

Kay tried to follow his directions and meet with His Holiness, but just did not know how to arrange it, and after a couple of weeks returned home. The meeting would occur a year later. When we sought the Dalai Lama’s advice he told us to do what became a three month-long meditation retreat in the guest house of his monastery. We had never done one on our own, so I asked for a recommendation of someone to guide our retreat. He suggested Denma Locho Rinpoche, who in time became both Kay’s and my next personal lama. (See: A Now Which is Outside of Time.)

Tara Tulku’s slow and steady nurturing of my inner “spiritual life” over many years and his remarkable kindness and compassion had produced a (metaphorically) young plant. Denma Locho Rinpoche would continue to nurture that plant until it began to blossom into inner realizations I could not have imagined in my wildest dreams.

Could I have maintained my meditation practice over the years without my devotion to these two lamas? I sincerely doubt it. But where had this devotion sprung? Why had these lamas given me so much of their time and wisdom, encouraged me when necessary and kicked my butt when necessary. Several years after becoming his disciples Locho Rinpoche invited Kay and I to his residence in Dharamsala to receive daily teachings. I asked why had we been so fortunate? His answer was both simple and profound. “Because we have all practiced [meditation] together in past lives.”